|

A hundred years ago, drinking establishments were sprinkled throughout inner northeast Portland, which was then a separate city called Albina. Kegs were stored under the bar, and beer was drawn by a brass pressure tap or by a gravity faucet inserted directly in the keg. Men stood at the bar, as stools did not come into use until after Prohibition.

Prohibition was not well-received by many of the Volga German immigrants who lived in the neighborhood. Elder Peter Yost of the Free Evangelical Brethren Church reportedly gave his greatest sermon during this time, complaining that "food" was being taken away from his people. In many families, it was common to send a young child to the tavern with a tin pail to fetch beer to drink with dinner. The bar-tender would fill the pail and the child would carry it home, careful not to spill a drop. The photo below, courtesy of Shanna Minarik, shows the Ludwig Miller Saloon (circa 1913) which was located at 740 Union Avenue, now known as Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd. This story is condensed from a longer version published on the volgagermans.net website, courtesy of Steve Schreiber.

0 Comments

The Sabin mural was painted in 1996 by Isaka Shamsud-Din, with the assistance of apprentices and volunteers. Learn more about it at Linda Wysong's Sabin blog.

Caution, don't visit the Vintage Portland blog unless you want to fall into a black hole of Portland history.

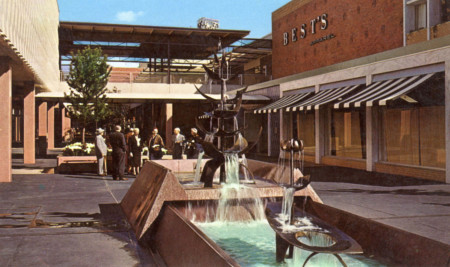

But, if that sounds like fun to you, check out these photos of northeast Portland in the olden days. Courtesy of Vintage Portland and the City of Portland Archives, here are a locations you may recognize...

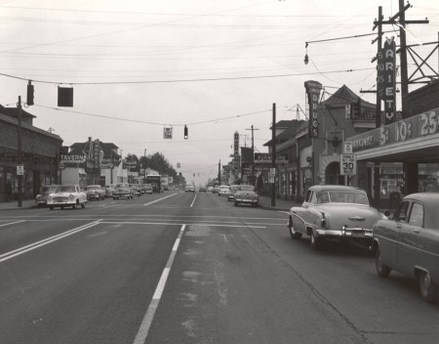

On Saturday afternoons and evenings, I sold the Journal’s Sunday edition from a prime location – in front of the Oregon Liquor Store, between Fremont and Beech on NE Union Avenue, which is now Martin Luther

King Jr. Blvd. The foot traffic was heavy, not only because of the liquor store, but also because Bihn’s Lincoln Park Market was next door. That was where many Volga Germans purchased Bihn's famous smoked German sausage links – a Saturday dinner ritual. On Sunday, December 7, 1941, the Oregon Journal printed a special edition due to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. I stood on the southwest corner of Fremont Street and Williams Avenue because there was a stop sign there. When a car stopped, I held out the paper and shouted, “Extra, extra, read all about it!” The paper sold for three cents a copy and many a customer gave me a nickel, and told me to keep the change. Story condensed from a longer version by Mel Cook and published on the volgagermans.net website, courtesy of Steve Schreiber. More memories from former Sabin resident Mel Cook:

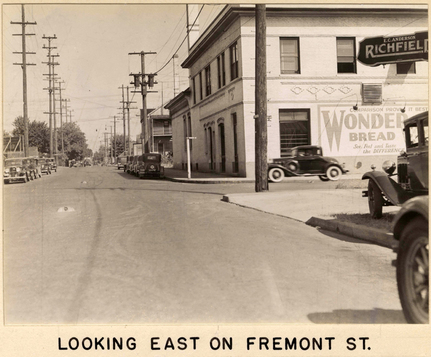

During the Great Depression, my grandfather, Henry Koch, lived at 3963 Northeast 14th Avenue. He would leave early in the morning and walk to the Wonder Bread Retail Outlet to purchase day-old bread and pastries. If he was late getting there, the shelves would be bare. Because of the reduced prices, that Retail Outlet was a Godsend to many people in the Albina District. As a child, I lived directly across the street from the Wonder Bread Bakery, at 101 North Fremont Street, between Williams and Vancouver Avenues. I can remember being allowed to wander through that bakery and talk to the workers at the dough-mixing, baking oven, and packaging stations. Those men were very proud of their work and were more than willing to take the time to explain what was happening at each station. Can you imagine that freedom of entry and communication taking place today? This story is condensed from a longer version written by Mel Cook and published on Steve Schreiber's volgagermans.net website. OK, the Fremont Market wasn't located in Sabin, but very close. From the mid-1940s till the late 1960s, it was situated on the southwest corner at the intersection of Williams Avenue and NE Fremont Street. The market included an old-fashioned butcher shop and the owner, John Sinner, was famous for his German sausage. The site is now a New Seasons Market, which periodically makes and sells sausage using John Sinner's recipe.

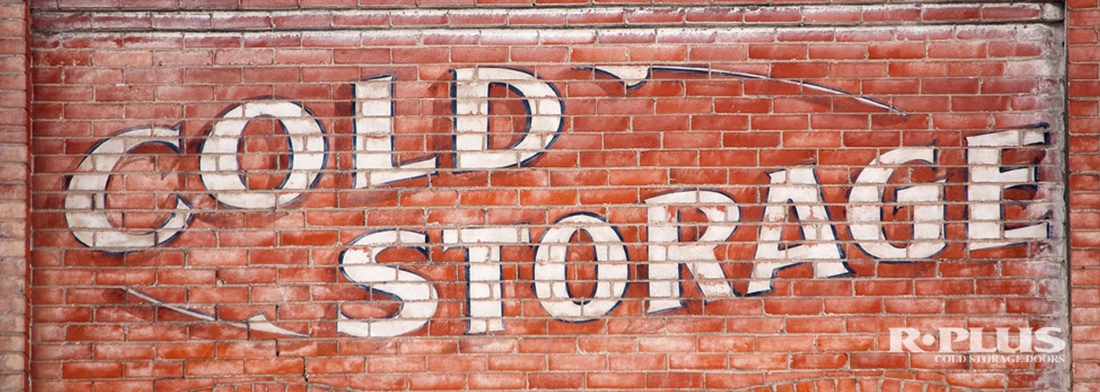

Article condensed from a longer version accessible on volgagermans.net, courtesy of Steve Schreiber. Updated 9/13/2015. Original source: Lisa Sinner Hetzler (daughter of John and Frances Sinner) Georgia (Koch) Thomas remembers the cold storage lockers that were located on the SW corner of NE 10th and Beech: “In the 1940's and early 50's most of us didn't have freezers, so our moms rented space for our supply of meat and poultry. That was always a great place to go to on a hot summer day!”

Mel Cook recalls helping to build that cold storage locker. “During one grade school summer vacation, I can recall stuffing shredded redwood bark into the open spaces in the newly constructed cold room walls. That was the preferred method of insulating at the time, many years before fiberglass insulation became popular. The redwood bark had to be finely shredded prior to hand-stuffing into the open wall spaces. The mechanical shredding process that we used was very messy. I wore a handkerchief across my nose and mouth. The fine particles became imbedded in my hair and clothes. I itched for days!” Mel continues: “I do not know how many years that cold storage food locker was open for business. With the advent of home freezers, it is likely they were forced to close sometime during the 1950s or 60s. Today, at that same 936 N.E. Beech Street address, you will find the New Freedom Assembly Church of God In Christ.” A longer version of Mel's story is published on Steve Schreiber's volgagermans.net website. The neighborhoods now known as Sabin and King were once dotted with small grocery stores, many built by German-speaking immigrants from the Volga region of Russia. One of those businesses was Lehl and Popp Grocery, co-located with Schnell's Meat Market in a building at NE 10th and Failing, which burned down in the 1960s.

Conrad Brill was born in the Russian village of Norka in 1895 and relocated with his family to inner NE Portland in 1922. In his memoirs, he recalled: “There were several of our fellow Volga Germans in the grocery and/or meat business. Like most grocers of those days, they did most of their business on credit. When you paid your grocery bill, you usually got a cigar and a sack of penny candy to take home to the children. The grocer had wooden barrels of dill pickles, sauerkraut, pickled pigs feet, drums of kerosene, 100-pound bags of potatoes, sugar, flour, rice and beans. He bought from wholesalers, farmers and even neighbors who had good fruit, berries or vegetables. Farmers brought eggs and live chickens, usually on Thursday afternoon or Friday morning. Potatoes were sold by the peck, or bushel, rather than the pound. Fruit was sold that way too. Any bulk items, which came in barrels, could be bought by any amount you wanted, scooped into a grocery bag. There were hundreds of Grade A raw milk dairies around and the price of milk was six cents a quart.” Read more about Conrad's memories on volgagermans.net, created by local historian (and former Sabin resident) Steve Schreiber.

Gas was 10 to 12 cents a gallon, depending on the grade. It brought customers into the station, but the “real money-makers” were oil changes, engine tune-ups and repairs. Mel recalls: “Every Saturday, which was the day I received my pay in cash, my first destination after work was Watkins Drugstore, located on the southwest corner of Failing and Union Avenue (now Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd). There, I would reward myself with a most wanted indulgence, a butterscotch sundae, topped with whip cream and a cherry. I am not certain of the exact cost, but I would guess it was in the 15 to 25 cent range. Delicious memories

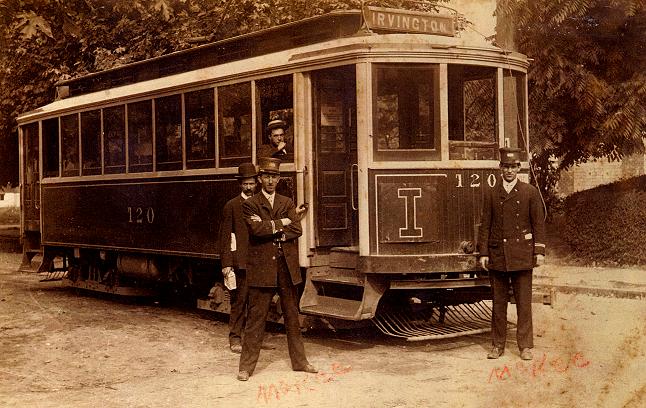

of youth are still with us, no matter what our age may be.” This story is condensed from a longer version written by Mel Cook, and captured on Steve Schreiber's volgagermans.net website. In the early days, most people in Portland lived within a mile or two of the city and walked everywhere. Then, in 1872, Ben Holladay built the city’s first horse-drawn streetcar line, which ran along First Street. According to historian Mark Moore, “the early horse-drawn streetcars were soon joined by and later replaced by steam trains and eventually electric trolleys. Portland’s first electric streetcar took to the rails in 1889 and carried passengers across the Steel Bridge to the town of Albina.”

Moore explains that the expanding streetcar lines allowed residents to live farther from the center of the town. “Real estate developers created the communities of Council Crest, Hawthorne, Irvington and Mount Tabor, as well as others, as the streetcar lines lured people away from the central city to live in the suburbs.” The Irvington streetcar line originally came across the Steel Bridge, went north on Grand, east on Multnomah, north on 15th, then ran east on Tillamook. In 1910, the east turn at Tillamook was abandoned and instead the car continued north to Siskiyou. In 1913, the line was extended further north to Prescott. Historian Richard Thompson notes that,“by the time ridership peaked in 1922, street railways had become more than a means of transportation. During hot summer evenings, families relaxed in open cars; and on Sundays, people rode to the end of the line for a day of picnicking, hiking, or fishing. Trolley parks such as Council Crest and Oaks Park offered attractions including amusement rides, dance bands, and roller skating. People also rode streetcars to racetracks, golf courses, and beaches.” Thompson explains: “Affordable automobiles, better roads, and the rising cost of labor eventually changed all of that. By the late 1920s, people were increasingly envious of the freedom and status that came with owning an automobile... The last three city streetcar lines were converted to bus operation in 1950 and the final interurban line ceased operating in 1958.” The Irvington line was converted to bus in 1940. Sources: Mark Moore – pdxhistory.com Richard Thompson –oregonencyclopedia.org Portland Vintage Trolleys – vintagetrolleys.com Carl Townsend – irvingtonpdx.com |

Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed